My family tree is not lush and bountiful. Instead, its branches have been savagely pruned; sometimes entire limbs were sheared off by the Darwinian forces at play in Scotland’s far north. Traditionally, whisky production and fishing were the main livelihoods, meaning that those who didn’t succumb to the sea were liable to drink themselves to death. When I was a young boy, my mother would tell me stories about her homeland. My eyes opened wide as she regaled me with tales of hairy cows, vast moors of mist-drenched heather and men who wore skirts yet had the fortitude to stare down the Romans.

I was intrigued by this distant nation, awed by my mother’s stories, and I knew that, through my heritage, I was indelibly connected to Scotland. Along with the tales of Robert Louis Stevenson told to me as I drifted to sleep, my mother’s Scotland was filed in the part of my memory reserved for fiction, fantasy and folklore. And like the children in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, I felt I had a secret connection to another world. I was sure that one day I would make that journey.

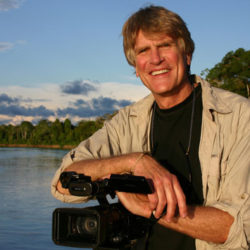

That day arrived in early March 2008. My wife, Julie, and I slipped over the border from England in a rental Dodge Caravan with two homemade rowboats strapped to the roof. The interior of the vehicle was in shambles, jammed to the ceiling with camping gear, bicycles, cameras, oars and a miscellany of other equipment. As we ventured farther north, following single-track lanes through unpopulated moors, horizontal rain and gale-force winds buffeted our top-heavy vehicle. Dark clouds scudded towards the elongated black hole of a horizon, and sodden sheep stood with their rumps to the wind.

“It was a really gay day, wasn’t it?” Julie said, breaking an extended period of silence.

“What was a gay day?”

“The day we decided to do this trip.”

I wasn’t sure if she meant it was a happy day, which it was, or if the decision we made that day, which led to committing ourselves to a desolate, freezing world with only a tent for shelter and 7,000 kilometres to travel using only our arms and legs, was a dumb idea. A South Park kind of gay.

I slowed the vehicle to allow a mass of soggy wool to cross the road. The trailing shepherd nodded to us, his face lost in the shadowy folds of a black poncho.

“I suppose so,” I said. “I’m sure this weather will clear up shortly.”

We’d come up with the idea for this journey two years earlier on a sunny day in Germany. At that time, Julie and I were engaged and were inadvertently testing the bonds of our relationship by travelling together from Moscow to Vancouver solely by human power. The crux of the expedition was a 10,000-kilometre row (yes, row, as in propelling a tippy little boat on a pond) across the Atlantic Ocean. As we cycled across Europe, most of our thoughts were focused on the maritime challenge ahead, instead of the rich cultures, landscapes and architecture around us. And because of the urgency of reaching the Atlantic Ocean ahead of the stormy season, our route was mainly confined to busy highways.

On occasion, these vast ribbons of fumy asphalt traversed rivers or canals, and we paused on the bridges to observe the scene below. River barges, rowboats and sailing dinghies plied murky waters bordered by orchards, farm fields and stone villages. Paths often flanked these waterways, and we watched enviously as cyclists followed meandering courses to nowhere.

We noticed the road atlas we were using to navigate across Europe also outlined the waterways, and closer examination revealed Europe’ s labyrinth of water corridors. Julie traced a route of interconnected canals, rivers and coastlines that led from my parents’ homeland of Scotland past her mother’s home in Germany and on to Syria, where her father comes from. We could paddle all the way from Scotland to Syria and visit our relatives, she said half-seriously.

Whether this comment was made in jest or not, a seed was planted. Over the following months, we researched the possibility of paddling or rowing from Britain to the Middle East. My family comes from Caithness in Scotland’s most northeastern corner, so this was where we would start. From there, we could follow a network of canals, lakes, rivers and shorelines all the way through Britain to Dover. We’d row across the English Channel, then journey into Europe’s interior by paddling up the Rhine River or navigating France’s extensive network of canals. The European continental divide would be crossed on the manmade Rhine-Main-Danube Canal, which connects the Rhine River and the Danube. And once the headwaters of the Danube were reached, it would be possible to voyage downstream to the Black Sea, through the Bosporus and finally on the Mediterranean to Syria.

The plan appealed to our sense of adventure, but more importantly it promised to be a journey that would allow us to explore our roots in a more compelling fashion than a quick online genealogy search followed by a two-week tour package being bused to tourist shops selling stuffed Loch Ness monsters, Middle Eastern rugs and the made-in-China American Indian knick-knacks. No, this would be a seat-of-your-pants adventure that would immerse Julie and me into the cultural and physical forces that had shaped our families and made us who we are. It would give us greater perspective not only on our heritage but also on the distances and lands separating the regions we come from.

The more we researched, though, the more we unearthed questions we could not answer. Would we be able to make our way against the swift current of the Rhine River? Would a human-powered craft be allowed to navigate the canal locks that are normally used by power boats? How difficult would voyaging the British coast be in late winter?

There was too much uncertainty, and although it was theoretically possible to travel on water for every inch of the journey, we felt an efficient portage system was required. Julie and I pondered the various possibilities, from lightweight canoes with padded yokes to sea kayaks and rugged dollies. We came to the conclusion that nothing on the market met our needs.

“Maybe we could tow our boats behind bicycles,” Julie said, thinking of the trailer she uses for cycling home with a heavy load of groceries.

It seemed like a practical idea except for one thing: what would we do with the bikes and trailers while on the water? A sea kayak doesn’t have the cargo capacity to carry such a load. While a canoe could easily carry a bicycle, it lacks the seaworthiness to cope with some of the rougher coastlines we planned on paddling. We considered using a dory, which is seaworthy and has sufficient cargo capacity, but decided the weight would be prohibitive. Eventually, we realized the ideal boats had yet to be made. We would have to make them ourselves.

We designed the boats and built them in the backyard with plywood and fibreglass. They looked like large sea kayaks, but had sufficient cargo space to carry our bicycles, trailers and all our camping gear within sealed compartments. The boats were shaped so that in the event they capsized, all the water would drain from the cockpit when they were righted. They were also decked with watertight hatches, ensuring the equipment would stay dry in big waves or in the event of a capsize. As a finishing touch, we created a system that would allow them to be joined together as a catamaran with a platform large enough to erect the tent on. This arrangement would allow us to camp in urban areas where conventional tenting was not an option.

We chose a sliding-seat rowing set-up because it provides much more power than paddling and would allow us to propel our burdened boats easily and quickly through the water. It also offers a full-body workout, exercising not just the arms and shoulders but also the back, stomach, buttocks and legs. If we were going to spend six months in a boat, we reasoned, we might as well get fit in the process.

The trailers were custom made by Tony Hoar, a Vancouver Islander who specializes in making unique bicycle trailers. They were designed to disassemble and fit in the boats’ centre compartment along with the bicycle. But despite our best efforts to build quality vessels, we worried that our amateur-built craft might not be up to a 7,000-kilometre journey.

Now, as Julie and I drove in inky darkness with the boats on the roof of the van shifting dangerously in the heavy winds, I prayed our homemade contraptions would be able to withstand the rigours ahead. The vulnerability of their thin plywood bodies was accentuated in a world where stone seemed to offer the only true defence against the North Atlantic’s wrath. As if to further emphasize the point, the crosswinds intensified, and we were forced to stop the van in the middle of nowhere to avoid losing our rooftop cargo. We had no choice but to wait for the weather to improve, and so we spread our sleeping bags in the back and fell asleep in the violently shaking vehicle.

The following morning, we reached our destination, Castletown, a village of about three thousand located six kilometres from mainland Britain’s northernmost point. The surrounding landscape was a rocky moor with occasional stunted trees and pastureland. Swollen steel-grey waves collapsed onto a jagged shoreline next to the town, and wind snaked through the streets, lifting dust and rattling windows. The flagstone buildings were indifferent to gusts that almost bowled us over.

Although my mother and father were born in Edinburgh and Glasgow respectively, their roots lie here. Castletown was where my paternal grandfather lived, descended from a line of shipbuilders and fishermen, while my maternal grandfather came from Wick, a coastal town 20 kilometres away. Between these two communities in the tiny oceanside hamlet of Keiss reside the last of my known relatives in this region. We checked into the town’s sole hotel, a Victorian-era stone building.

“Sinclair?” the proprietor said, noting my middle name in my passport. “I have a good friend, Peter Sinclair, in Keiss.”

Of course. That’s how it is in these tight-knit communities. Peter Sinclair is my second cousin, the son of my mother’ s aunt. Coincidentally, the name Sinclair is my paternal grandmother’s maiden name, but there is no known blood connection from my father’s side. I would soon be meeting this branch of my family for the first time. As well, my half-sister Betti Angus would be joining us, making her way up from her home outside Glasgow. Betti and I are linked through paternal blood, but I had met her only once, when I was twenty-five. She was still an enigma. It has always seemed odd to me that I have a sister who speaks with a broad Scottish accent, and I was pleased that she had offered to join us as we sleuthed to understand our origins.

Our hotel, the St. Clair Arms, was surprisingly comfortable considering its modest price and remote location. Decorative wallpaper and colourful bedding created a welcome contrast to the cold world outside. As Julie and I sorted our equipment, a knock on the door announced Betti’s arrival.

Betti was born two years before me, also in Victoria, British Columbia. Her parents divorced when she was an infant, and her mother had not been able bring up a child on her own. Our father, being a sea captain, could not look after Betti, so she was adopted by his childless sister and brother-in-law. Betti was raised an only child on the tiny Isle of Islay in the Inner Hebrides, a world away from her birthplace on Vancouver Island.

Julie opened the door and Betti welcomed us with bear hugs. As with the last time I saw her, I was struck by her resemblance to the man who sired us. She had his elfin features and sandy hair, but it was the shape of her sea-blue eyes that was most strikingly similar.

That evening my mother’s cousin Helen, her son, Peter, and his wife and children made the short trip from Keiss to meet us in the cozy hotel pub. I’d never before met this branch of my family, and I wondered if they were the tougher ones–those who didn’t flee the gales, rain and midges of Caithness.

Helen was rotund and kindly, while her son, Peter, in his mid-forties, had the robust build that comes from years of lobster-fishing in open boats. Over glasses of whisky, the stories began to flow.

“You’ve probably noticed there’s a disproportionate number of Sinclairs in the ground to the ones alive today,” Peter said, gesturing south towards the cemetery. “Aye, there were many scrapping clans around here, and we didn’t always fare so well in battle. The last clan war involving our family took place over a hundred years ago with the Campbells.”

The waiter paused by the table, eager to hear the story he probably already knew.

“They had a cunning plan to subdue us Sinclairs. A cask of whisky was dropped in the burn above our village. Of course, the Sinclairs fished it out, thinking it was a gift from the gods. The party began, the whisky was drunk, and . . . Well, that’s when the Campbells came with swords raised.

“Only those already dropped by the drink were spared. Saved by the whisky!” Peter laughed, holding his glass high.

Only a Scotsman could draw this moral from a story where heavy drinking precipitated a family massacre. It seemed the natural laws of evolution here had been rewritten by the folks at the local distillery.

“Saved by the whisky,” I said, toasting with another shot of its good self.

Before my grandparents’ era, migration was limited, and so it can be assumed that my family was partially descended from tribes that settled this region around 3500—4000 BC. These Stone Age hunters, gatherers and rudimentary farmers migrated from Continental Europe following the retreat of the last Ice Age. Lower sea levels exposed a land bridge that connected what are now Britain and France, and which humans began crossing around 9500 BC.

On the nearby Orkney Islands, just 25 kilometres from where our family sat enjoying a meal of haggis, mashed turnips and roast beef, lay Europe’s best-preserved neolithic village. Ten houses still stood in the settlement of Skara Brae, which was occupied from 3100 until 2500 BC. The homes were constructed of flagstone, driftwood, whalebone and turf-thatched roofs, and were partially built into the ground with mounds of dirt piled on top for protection from the gales. The islands are also home to four-thousand-year-old stone circles, which are thought to have been used for astrological observations and pagan ceremonies. The best-known in the region, the Ring of Brodgar, contains sixty stones in a 104-metre-diameter circle.

Eventually, the tribes of northern Britain formed a loose confederation and were known by the Romans as Picts, meaning tattooed or painted people. The Picts were fierce fighters and were successful in fending off many invading cultures, including the heavily disciplined Romans.

The next major wave of immigration wasn’t until 500 AD, when the Celtic people came over from Ireland and settled in western Scotland. The Celts originated from Continental Europe in the lands north of the Alps (as portrayed in the famous Asterix cartoons), and two groups migrated to lower Britain and Ireland, but only those from Ireland made their way into Scotland. There, they intermarried with the local people, and Scotland became a mix of the original indigenous population and Celts.

The Vikings were next on the scene, and these seafaring ruffians were a significant cultural influence in Caithness and the Orkney Islands. Beginning in 793 AD, Norwegian warriors launched a wave of invasions against Scotland and England. Amid their pillaging, they also established settlements, taking local women as their wives and farming the land. Caithness was the area most heavily populated by Vikings, and my family’s names speak of these and other ethnic influences.

Swanson, my great-great-grandmother’ s name, is Norwegian in origin (originally Svensson) and was introduced during the Viking conquests. Angus is an ancient Celtic name (originally Aonghus), meaning one choice. It is prevalent as a surname across Scotland, but most abundantly in Caithness. My mother’s family name, Bremner, is Flemish (meaning weaver) and was possibly introduced when a group of Dutch settlers were invited to the region in the 1490s to operate the ferry service to the Orkney Islands. These settlers included the founder of the ferry system, Jan de Groot, after whom John o’ Groats is named.

As I looked at my family members seated around our table, I pondered the complex chain of events that had brought us all here. I was snapped out of my historical reverie by a rather startling question from Peter.

“Do you know anything about our rampant cock?” he asked.

Helen frowned at her son.

“No, tell us about him,” Julie said, her interest in my family history suddenly piqued.

“It’s not a he, it’s an it,” Peter said. “An animal.”

I groaned inwardly. This was it; Julie was going to start hearing sordid tales of what goes on in this remote region during the dark days of winter.

“It’s part of our family crest, the rampant cock. The Sinclairs possess the same strength and grit as a tough old rooster. And the clan motto is Commit thy work to God.”

The family profession of lobster-fishing certainly spoke of this fortitude. Peter’s deceased father had been a full-time lobster fisherman, but dwindling stocks meant his son needed to augment the family trade with work on the North Sea oil rigs. Currently, the crustaceans were in reasonable supply, and early the next morning Peter would drop traps in the Pentland Firth, the body of water between the mainland and the Orkney Islands.

I asked him if he was concerned about the forecasted 70 kilometre an hour winds and 12-metre swells.

“Nay,” he said casually. “It’s always like that. You get used to it after a while. Besides, we look after each other. The biggest danger is blowing a motor and getting raked over the rocks, but most likely you’d get a tow from another boat before that’d happen.”

In the past three days, the swell hadn’t dropped below eight metres. Julie and I had watched in awe as liquid mountains exploded against rocky headlands, sending plumes of aerated water 30 metres into the sky. I was relieved our trailers and bicycles gave us the option of travelling overland on our own journey.

The following morning, while Peter braved the Pentland Firth, Betti, Julie and I went to visit the cemetery, just south of the village. The disused burial ground could have been a set from a Bela Lugosi movie. Crows eyed us from perches in skeletal branches of wind-sculpted trees as we walked between eroded tombstones. An abandoned church, its roof caved inwards, lay at one end of the property, and a disintegrating wall lined the premises. Dates on the legible stones ranged from the 1700s to the 1920s.

Betti pointed out the graves of distant relatives. I was struck by the prevalence of our family names; it seemed half the stones had Sinclair, Angus or Bremner etched into their pitted surfaces. I tiptoed gently over my long-decomposed family.

“What kind of stone are these made from?” I asked Betti, pointing to the roughly cut marker stones.

“Flagstone. The same as what the entire town is made of. It protects us in life and guards us when we fall.”

“For a while,” said Julie, eying a toppled stone with a weather-obliterated inscription.

Flagstone from this region wasn’t used just for building around Castletown. During the 1800s, local quarries created a huge boost for the economy when the layered sedimentary rock became a popular building material in southern Britain. It is said that all the roads of London were paved with Castletown flagstone in the mid-1800s. Eventually, demand ceased, and now the quarries are silent, surrounded by rusting machinery and mounds of flat, cracked stone.

The local library contained a compilation of census and wedding records for the region. Through these statistics, and Betti’ s earlier sleuthing, we traced my father’s side of the family back to the 1700s. The records showed many marriages between the Sinclair and Angus families through the generations. “Da, na, na na na na . . .” As she studied the names, Julie hummed the banjo tune played by the inbred kid in Deliverance. “Look, I think they made a mistake here,” she said. She was pointing to the marriage of William Angus to Margaret Angus in 1741. “They put her married name instead of her maiden name.”

“I don’t think it’s a mistake,” I said. “But that’s how it worked with the clans. They all married each other. Otherwise they wouldn’t be clans, would they? It doesn’t mean they were brother and sister. There were probably more than a thousand Anguses in the clan.”

“Da, na, na na na na na . . .” hummed Julie. “Can you play that tune on the bagpipes? Or were your clan members too busy playing with each other’s rampant roosters to learn any instruments?”