Okay, it’s been a little while, but here’s the trip summary. Things have been pretty busy since being home catching up.

Must say it’s great not having to get up each morning at 3:00 am. Below, I’ve posted the summary of the trip.

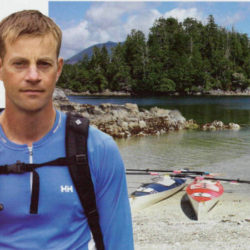

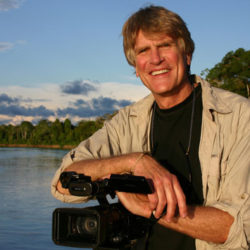

In June 20, 2011 Colin Angus departed from Comox, BC in an attempt to break the record of circumnavigating Vancouver Island by human power. This would involve paddling/rowing more than 70 km/day for more than two weeks through some of the most challenging ocean conditions in Canada. Traditionally, the record has been held by kayakers, but Colin attempted it in a rowboat he designed and built himself. 15 days, 11 hours, and 47 minutes after beginning Colin returned to Comox successfully completing his 1100 km voyage and breaking the record. A big thanks goes to the many supporters of the expedition including Sundog Eyewear, Iridium Satellite systems, and Helly Hansen. Additionally, Colin would like to thank his wife, Julie Angus, for being a pillar of support, along with the many people who cheered him on his way. Below Colin describes the journey.

Rockin’ and a Rowin’ around Vancouver Island

A few hours from the end of my record-breaking voyage, I pulled into Ford’s Cove marina on Hornby Island. The day was going smoothly, and a couple slices of pizza and a cappuccino seemed a suitable way to celebrate my last few hours on the water. As I tied my peculiar-looking rowboat to the dock a tourist looked over with interest.

“Where’d you paddle from?” He asked.

“Comox.”

“That’s a long way to travel in a small boat,” He said, scrutinizing my vessel with renewed interest.

He was obviously thinking the direct route from Comox – about 27 km. At this point, I’d actually rowed almost 1100 km from Comox as I circumnavigated Vancouver Island in a counterclockwise direction. The remaining 27 km distance seemed a skip and a hop away.

My spirits were buoyed by thoughts of completion and the great weather, but it hadn’t always been fair winds and flat seas.

My voyage started at 4:00 AM, June 20 from a beach in Comox. It was dark, and together, with my wife, Julie, and our crying nine-month-old son, Leif, we launched my 18’ rowboat into the choppy waters. A stiff breeze blew from the north, and as I strained at the oars I couldn’t help but wonder what I’d gotten myself into.

Two years earlier, when I first announced that I planned on trying to break the human powered speed record around Vancouver Island it seemed like a good idea. I lived on the Island, enjoyed being on the water, and had plenty of experience executing human powered journeys. The only problem, however, is I’d never done any true endurance trials. My long-distance cycling and paddling endeavours had always been at a relatively comfortable pace; if the muscles ached, I’d slow down correspondingly. My journey around the island would teach me very quickly what my true limits of endurance would be.

The first four days heading north through the calm waters of the Johnstone Strait went relatively well. Plenty of favorable currents helped me on my way, and rugged scenery and varied wildlife provided entertainment. North of Campbell River human habitation all but disappeared and I was crowded by steep mountains along the western shore and lush islands to the east. Porpoises, killer whales and seals became my closest companions.

Sometimes the currents created strong rips or conjured ornery standing waves against contrary winds, but I knew these hazards would be mild compared to what I would face on the west side of Vancouver Island. I passed through Seymour Narrows when the current was flowing at eight knots (about 15 km/hr), and bounced through boils, small whirlpools and churning eddy lines. Seymour narrows has some of the strongest tidal flows in the world, often peaking at 15 knots.

The rowing routine comprised of one hour sessions pulling on the oars followed by 5-10 minute breaks resting, stretching and snacking. Energy expenditure is high when rowing, so it was important to consume significant calories in the form of granola bars, dried fruits, nuts, crackers candy, chips, and great volumes of mayonnaise.

I would row until fatigued, usually about 12 hours in total, and then look for a suitable place to camp. Ideal campsites had some sort of beach to drag the boat up on, and sufficient clear area above the high-water line to set up the tent. A fresh water source was a bonus; however, I usually carried two days surplus water in the boat which offered more freedom in finding camping sites.

By the end of my fourth day, I reached Experimental Bight, the most northern beach on Vancouver Island on the east side of Cape Scott. Cape Scott is a region of lush rainforests, long sandy beaches and rocky headlands. The beauty is often overshadowed by the ferocity of the weather. In 1870 these lands were settled by Danish immigrants. Despite heroic homesteading efforts, bad weather and isolation conspired against the Danes, and eventually they gave up. There is still plenty of evidence of their presence, and not far from my tent the decaying fence posts marking the edge of their pastures could be seen.

Fortunately, the weather was good for me and the following morning I rounded the northwestern tip of Vancouver Island, and pointed my boat southwards. The sheltered waters of the Inside Passage were behind me, and I was exposed to the full swell of the open Pacific Ocean.

My introduction to the open Pacific was relatively calm, and I was able to make my way safely to a small island fronting Lawn Point Provincial park where I could pull my boat up in sheltered waters. The tiny islet was tufted with a few wind-sculpted fir and cedar trees, and the rocks were bejewelled with an assortment of flowers that could have been part of Butchart Gardens. Lawn Point, just a few kms away lived up to its name and was carpeted with thick green grass. It resembled a golf course, and I wondered what conditions prevented trees from growing on the point.

There was no water on my island, but fortunately I carried two days of water in the boat, carried from Cape Scott. Although there were no streams near my campsite in Cape Scott, I had been able to eke the water from a swamp by digging a small hole.

Brooks Peninsula and Solander Island, 25 km distant, were clearly visible from my campsite, and I kept my fingers crossed that the weather would hold. Brooks Peninsula and Cape Cook off its northwestern tip were labeled by Captain Cook as the Cape of storms. It juts out from Vancouver Island and compresses the prevailing winds and currents, often creating nasty weather conditions. Additionally, waves reflecting off the cliffs, shallow waters, and hundreds of submerged reefs can create a paddling nightmare.

To avoid the worst conditions, I plotted a route that would take me well out to sea, and into less turbulent waters. The main drawback with a rowboat is the rear vantage, and it can be difficult spotting lethal submerged reefs (also known as boomers) which are only occasionally visible when large waves break over them. Kayakers can generally avoid boomers by sight alone; however, this wouldn’t be safe in a rowboat. Instead, prior to leaving home, I plotted a course down the entire west coast that would steer me safely through the boomers. I inputted about 60 waypoints into the GPS, and my safety would rely on travelling from waypoint to waypoint, directed by the digital arrow in my GPS. As I looked at the powerful waves exploding over reefs around my island, I hoped that I hadn’t made any mistakes in my data inputting.

As usual, I dragged myself from my warm sleeping bag at 3:00 am and was off the gravelly beach by 4:30 to take advantage of the calmer morning conditions. In three hours I reached the outside of Solander Island, and entered the turbulent seas off Brooks Peninsula. A northwest wind was picking up and waves reflecting off the cliffs collided with the incoming swells from the sea. The overall effect was a confused explosive chop, tossing my small boat in all directions, and arresting any attempts in gaining momentum. Eventually, however, as I passed south of Solander, the seas became more regular, and my speed increased. The NW wind was in my favour, and soon large waves further assisted my progress. Wind speed increased close to gale force, and by four pm I finally pulled into shore, having logged a respectable 76 km.

With ominous Brooks behind me, I relaxed on another small islet where I went about my usual camping routine. First I would pull the boat and gear above the high tide line, and then celebrate the day with a milk and protein powder smoothie. I made my daily call to Julie on the Iridium Satellite Phone (I had no cell phone reception from Comox to Tofino) and relayed news of the day, set up the tent and then made dinner (instant mashed potatoes and boil in the bag curry). By the time the dishes were washed, it was time for bed.

Another day’s rowing brought me to Friendly Cove at the southern tip of Nootka Island. This sheltered bay is another location with a rich history. The village of Yukuot has been continuously inhabited for 4300 years, and about 1500 First Nations People resided here when the first Europeans arrived in the late 1700s. Captain Cook was the first European to step onto British Columbia shores at this location when his ships arrived in 1778. He and his crew remained for about a month while they conducted repairs. Later, in 1789 a church was built here by the Spanish.

Now, the site of the village is just a grassy meadow, and only the church remains. Just one family resides here, living on the outskirts of the original village site in a modern wooden house, energized by a rumbling generator.

I camped just below the village site on the beach with a clear view of the lighthouse, a couple of hundred metres away. A brief chat with a member of the coastguard stationed here marked the first face-to-face conversation I’d had in over a week.

The following day was the worst slog yet. I rounded Estevan Point into stiff headwinds and big seas. An exposed rocky shoreline meant I had to continue long beyond the point of exhaustion before finally reaching the sheltered waters of Openit Inlet by Flores Island. Tired and sore, I pulled up to a placid beach, shooed away a bear (the fourth I’d seen so far) and settled in for the night. The long day had been tough on my body, and severe tendinitis was setting into my wrist and legs.

Drizzle and fog greeted me the following morning. Fortunately, I was able to row a little easier through the sheltered waters of Clayoquot Sound. At 1:30 I reached the village of Tofino, and was thrilled to finally rendezvous with Julie and Leif. This was the first road access point I’d encountered in the last 400 km.

My time in Tofino was all too short, and we ran around cleaning up the boat, packing new supplies, entering waypoints into the GPS, and making a visit to the doctor. I had hoped to get cortisone injections, but the doctor didn’t think it would help. It takes about three days to become effective and can often aggravate the situation before relieving the inflammation.

I finally got to bed at 11:00 pm (my normal bedtime was about 7:30) and was up four hours later. I felt miserable, sore and cold as I departed into the rainy darkness. Two hours later, the pain of the tendonitis was too much and I pulled into a beach near Tofino, set up my tent, and dejectedly whiled away the day. The only distraction from my glum prospects was being able to watch a big black bear ambling along 100 metres from my tent.

The following morning things were no better. The tendons in my legs driving the sliding seat were still in severe pain and grated with every movement. At this point I had made excellent progress – taking 9 days to get from Comox to Tofino, and had been on track to break the record. I had to make the choice between throwing in the towel and carrying on. I decided I would give it my all, and from then on the days were clouded with some of the worst pain I’ve ever endured.

It took me three more days to make it to Victoria. I passed the entire length of the West Coast Trail in about eight hours. Timing my entry up the Juan de Fuca Stait had to be precise to take advantage of the tides. For 18 hours of the day strong currents flush out to sea, and the water only flowed in my favour for six hours each day. Gale-force winds and a rocky shoreline made for challenging but fun conditions. The rowboat surfs very well, and I caught some extraordinarily long rides on the steep powerful waves, clocking up to 20.5 km/hr.

From Victoria, conditions were a dream, and it took three more pain-filled days to make my way back to the Comox Valley. After finishing my cappuccino on Hornby Island, I climbed back into my boat for the final three-hour voyage back to where I started. The Comox Valley OC-1 club came out to greet me in their speedy paddle craft, and we all paddled together for the last few hundred metres. Julie, Leif and a crowd of family, friends and spectators awaited at the boat-launch ramp where the journey began.

15 days, 11 hours and 47 minutes after starting the circumnavigation around Vancouver Island was complete, and I had broken the previous record by a day. It was time to rest.