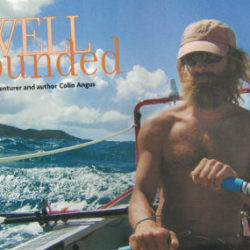

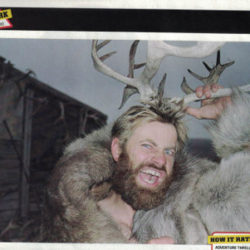

I pull my kayak onto the muddy riverbank, spark up a small fire from dry brush and begin my nightly ritual of foraging for food. For the past few days I’ve been living off rhubarb, wild onions and anything else I can scavenge along the shore of this valley in drought-plagued Mongolia. Driven by a nagging hunger, I scramble through the bush, a caricature of a castaway, Robinson Crusoe gone to seed. A scraggly beard disguises my sunburned face as I stagger around in dirty cotton pants and a pair of pogies – fingerless paddling gloves – worn like clown’s shoes to protect my feet.

Suddenly I startle a pigeon-sized bird from the base of a cliff. In its abandoned nest lie three eggs. They’re speckled, about half the size of a chicken’s and more valuable to me than any jewel-encrusted Faberge creation. I pick one up and gently crack it open. Within I can discern the network of veins from the partially formed fetus. I close my eyes, suppress a gag and swallow the contents. It tastes indescribably good. I briefly consider rationing the other two, but the shells are so delicate that I don’t want to risk breaking them on the journey. I gobble them down.

After the eggs, I crumple some stinging nettles into a ball, soak them in water and then roast them in the fire. I remember from some piece of summer-camp wisdom that cooked nettles are nutritious, and the result tastes like smoky spinach – surprisingly good. For desert, I slash a birch tree with my jackknife – my only tool other than my lighter – and lick the syrupy sap that issues forth. It’s hardly haute cuisine, but it keeps me going.

Water is my greatest concern. I have no way of treating it – no filter, no tablets. Along the entire Selenge River I’ve seen hundreds of the victims of Mongolia’s recent killer winter – horses, cows, sheep, yaks, camels – half-submerged on the banks or drifting, bloated, in the current. I worry that these putrefying carcasses might infect me with some extreme intestinal disease, but I have to drink something.

The three eggs may have stopped the rumbling in my belly, but as I sit on the fly-thick shore, my sunglass-less eyes still sting and my skin burns. Unfortunately, I know that dusk will bring a different discomfort. As the temperature nosedives, I’ll climb inside my kayak to escape from the cold and slide in as far as I can until only my head pokes out from the neoprene hole of the spray skirt.

Ever since I got separated from my expedition teammates, my life has been pared down to a grim case study from a wilderness survival manual. I feel as though I’ve been airdropped onto the set of an especially perilous reality-TV show, Survivor IV: The Mongolian Outback – minus the camera crew, the other contestants or any guarantee of a safe return home.

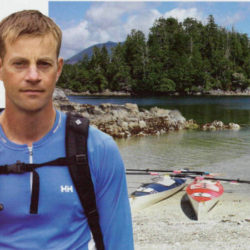

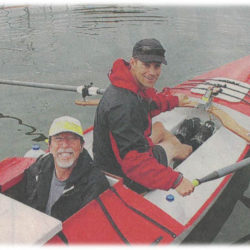

Until the capsizing, the journey had been going according to plan. Our three-man team had made good progress as we attempted to become the first people o run the Yenisey, the world’s fifth longest river at 5,500 km from source to sea. The waters that feed the Yenisey begin in the Hangayn Mountains of western Mongolia, rush down the Selenge River into Russia and Lake Baikal, and then flow northwards through Siberia to the Arctic Ocean. From Canada, we had shipped a 13-foot oar-rigged whitewater raft and two river kayaks to navigate the Mongolian portions, and in Russia we intended to switch to a traditional wooden dory for the flat water of the trip’s last half. At the town of Karaul, we’d hitch a ride west aboard a nuclear-powered icebreaker and then return to Beijing by train on the Trans-Siberian Railway.

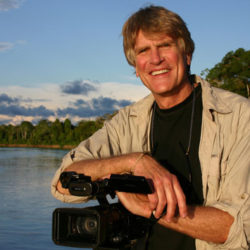

In early May, I joined Ben Kozel, an Australian friend with whom I’d rafted down the Amazon River two years ago, and Remy Quinter, a documentary filmmaker from Vancouver. After some bureaucratic hassles in Beijing (and losing my passport in Ulaan Baatar, Mongolia’s capital), we set off on our ambitious journey. We began by scrambling up the northeastern slopes of 13,000 foot Otgon Tenger, where we drank from tiny rivulets of melt water that marked the birthplace of the Yenisey River. We tracked these alpine trickles by foot until the water gained enough volume to set our boats in. By raft and kayak, we negotiated the toughest rapids of the upper tributaries and began to meander through some minor-league, class II splashy stuff. The worst whitewater, it seemed, was behind us. To increase our speed, we lashed the two kayaks onto the raft – the boat that carried all our belongings, all our food, all our money.

On June 3, 600 kilometres into our expedition, a flash flood ambushed us. A heat wave had rapidly melted the thickly packed alpine snow and the Selenge River had swollen quickly, soon breaking its banks. The glacial melt surged through the valley like a runaway streetcar. The flow of water we were following kept forking, splitting and braiding. Then suddenly it forked no more – the roiling water simply disappeared into a labyrinthine forest.

I was at the oars of the raft and the whitewater was more difficult than anything I’d encountered in my three years of rafting in the Canadian Rockies, on Vancouver Island and down the Amazon River. I struggled to control the boat as we sluiced at six knots through the flooded thicket, branches whipping at our arms and scratching our faces. Suddenly the raft struck a low-hanging tree limb before I could maneuver around it. We stopped briefly in the middle of the river, and then the force of the water gathered beneath us like a great fist and flipped the boat. Ben and I managed to scramble onto the tree while Remy swam after stray gear. The raft remained upside down in the water, its perimeter line snagged on the limb that had flipped it.

Remy splashed his way to an outcrop of land that protruded above the floodwaters, then made his way back and relayed the bad news: Our film bag had been swept away. All the cassettes, seven hours of vital footage for our documentary, were bobbing down the river. Without giving it much more thought, I slipped on my spray skirt, grabbed a paddle and jumped into the yellow kayak that we had freed from under the raft. I wasn’t going to let our film bag get away without a chase.

“Be careful, mate,” Ben said, as I slipped my kayak into the surging waters. The area of flooded forest stretched across two kilometres or so. Searching for the green dry-bag, I realized was like looking for a needle in all the haystacks of Mongolia. For all I knew, it could have been half way to the Arctic Ocean.

After several fruitless hours, I pulled my kayak onto the shore. Here the river flowed through a low canyon where the high banks could contain the swollen floodwaters. Ben and Remy were still upstream. I knew that if I waited here long enough, once they’d sorted out the overturned raft and retrieved the other gear, they’d drift by and pick me up.

————-

I’ve waited for two days. Now I’m beginning to worry. A scattering of nomadic herders populates the Selenge Valley, and I recall from the map that there is a village called Hutag about 100 km downstream. If Ben and Remy have passed my spot along the river unnoticed, as I suspect, then they’re likely waiting for me in Hutag. We’d agreed that if we should ever get separated, we’d rendezvous at the next town or village along the riverbank. I climb into my kayak and begin paddling. As dusk falls, I haven’t found my friends but discern along the shore the silhouettes of two nomads bending to their water urns. I wave as I approach and the men look up in surprise. “Sambano!” I yell. One of the young men returns the local greeting with suspicion.

I paddle to the bank and try to disarm their distrust with a broad smile as I nod at their battery of incomprehensible questions. They may be asking if I’m a Russian spy or have just landed from Mars for all I know. To win their trust, I step from the kayak and motion for the men to give it a go. Soon they are splashing about in the shallows, laughing at my strange boat, clapping me on the back. I feel a bit guilty, like I’m playing a fish, trying to gain their friendship only so they’ll feed me.

Finally, Tengle, the taller of the two, grabs my hand and beckons up to his ger, the kind of felt tent in which Mongolian herders live. The hook is set. I enter the warm smoky interior and Tengle’s wife, a robust woman of about 30 immediately hands me a bowl of Yak’s milk tea, followed by rice and horsemeat. I wolf it all down. Through a series of charades, Tengle invites me to spend the night there. I curl up under the yak skin and wonder where in Mongolia my friends are.

The following day, I set off after another filling meal of rice and horsemeat. The unrelenting sun has given me a mild case of sunstroke, so I carve a crude sombrero out of the kayak’s flotation foam. Tengle notices my blistered shoulders and gave me the shirt off his back – literally – I kiss him on the cheek.

My body is too weak to paddle much, so I float for 15 hours or so each day, doing my best to keep the kayak in the stronger currents, letting the river do most of the work. Two days after saying goodbye to Tengle and his family, I hear a shout from the shore and turn, certain it’s Ben and Remy. As I draw closer, though, I see three men fishing from the banks. One of them gestures to a green bag at his feet.

Incredible: It’s the film bag. We’ll have the documentary after all – if I ever find Ben and Remy. The contents of the bag are intact and dry, even after several days floating down the river. Along with our spent film and cassettes, the bag contains rolls of unused Kodak film and most importantly, a kayaking dry top, which will help protect me from the cold nights. The fishermen have no food, so I thank them and push off down the river again, the bag tucked into my kayak.

————-

Five days after the raft capsized, I spot the small town of Hutag shimmering along the shore in the midday sun. It seems like a mirage at first, an Asian stand-in for Dodge city: Horses are hitched to posts outside dilapidated Wild-West buildings, and I half expect to be greeted by an ornery nomad with a six-shooter and a 10-gallon hat – Genghis Wayne. I shoulder my kayak and stride down the dusty track between the wooden buildings. It’s high noon in Hutag, but there’s no sign of Ben or Remy.

A woman walks toward the river. She nearly drops her water urn when she notices me. Who’s the mirage now? “Sambano,” I smile. She averts her eyes and keeps walking. Eventually I find a store that contains racks of biscuits, corned beef, sardines and bread. I smile at the shopkeeper, point to the packs of flat breads and hold up two fingers. She places them on the counter and then writes on a slip of paper: 2,000 togrogs – about two dollars. I pull out a pack of five films. She shakes her head more vigorously, as if to say, “not for all the Kodachrome in the world”.

The bread in front of me was so close yet untouchable. I’m tempted to just grab it and do a runner. Instead I begin imploring her in English about how much that bread would mean to me, how many miles I’ve paddled to feast my eyes on her breadstuffs. Sick of my gibberish, she relents and lets me take it.

If I ration the bread to two pieces per meal, three meals per day, it will last me three days. With that – plus the rhubarb, nettles, and perhaps more nettles – I’ll eat like a king. I hit the river with renewed vigour and continued east. I’ve got to assume that Ben and Remy waited in Hutag for three days while I was idling upstream and then decided to push on for the next town, Suh Baatar. If I paddle long and hard, though, I can catch up with them. For the next fifty-five hours, I kayaked day and night – almost non-stop. I take one six-hour break on a windy afternoon to catch some much-needed sleep. By the time I reach Suh Baatar it’s been a week – and five hundred km – since I last saw my friends. I can’t wait to see them, to get a decent meal, clean clothes and some restful sleep – and to tell them my tale of mis-adventure. As my boat touches the shore in the pouring rain, I think to myself; What an incredible journey.

There’s just one problem; Ben and Remy aren’t here either.

The rain hammers down as I drag my kayak up the bank towards the train station. The people of Sur Baatar stop to stare at me – a bruised, soggy, shivering, shoeless spectre with a straggly beard. I’m not sure where I should begin to look for Ben and Remy. Sur Baatar is a sizable town, so I decide to check myself into a hotel where I can clean up, dry off, and leave the kayak in safety. At the brick hotel beside the train station, I’m refused a room; No passport, no togrogs, no service. Too cold and tired to begin the search for Remy and Ben, I return to the train station, place my kayak on the floor and take a seat. I hope that after a short nap the rain will have abated and I can begin the hunt for my friends. Surrounded by well-dressed Mongolians waiting for the train I fall into a fitful sleep.

“Passport!”

I wake up to the nudging of a police officer.

“My passport no here. Friends have passport,” I say.

“Passport!” the officer repeats.

Another policeman materializes from the shadows and stands menacingly by his side.

I hold my hands up in the air, “No passport! Oguee passport! Nyet passport!”

Finally they understand. The officer beckons for me to follow him, and at the far end of the station, I’m led into a dimly lit office. He points to a seat and I flop down as he settles his girth behind the opposite desk. We let ten minutes pass wordlessly before a young woman in army camouflage enters the office. The policeman says something to her, and then they both turn to me.

“Hello, Sir,” she says. They are the first two English words that I’ve heard strung together in what seems an eternity.

“Uh, hello, how are you doing,” I stuttered.

She smiles, “Not bad, thank you. Lieutenant Chentio want know why you here? Why no passport?”

Over the next hour, through broken English and hastily scrawled diagrams, I’m able to relay the gist of my story, and the policeman’s questions acquire a more sympathetic tone. He then leads me to the army base a block away and into another less spartan office. Two more men enter. One of them barks an order to a soldier, who disappears and then returns to my side with a tray of thickly buttered Russian black bread and a thermos of tea.

During the next three hours, the men debate what to do with me. Phone calls are made to Ulaan Baatar, to the head immigration office, even to the guesthouse where we stayed five weeks ago. They direct question upon question my way, the translator struggling with the complexity of the conversation, the strangeness of my answers. One thing is clear: Ben and Remy aren’t in town. The soldiers would have known of two foreigners arriving in a big yellow raft.

Finally they call an intermission, “We will finish this later,” the translator says.

She then leads me into yet and leads me into another office where I meet someone named Lieutenant Bolor. He is a pot-bellied man of twenty-five who slouches in an easy chair, feet on his desk, snoring. The room reeks of booze. The translator stirs the Lieutenant awake and he opens his rheumy eyes and stares at me until I come into focus. As sleep recedes from his brain, he addresses me in Russian.

“He is not Russian,” the translator says in English. “He is Canadian.”

“Hey man, how’s it going?” says Bolor in a mongrel American/Russian accent, “I don’t get to use my English too often.” It’s the best English I’ve heard spoken yet in Mongolia.”

“Are you hungry my friend? Come on, let’s get this man some decent food!” He yells some orders to a soldier by the door: Even when I talk quickly, Bolor understands everything I say. The only problem: He doesn’t seem too concerned about my predicament. I hoped he would assist as a translator, but Bolor has other interests.

“How do you drink in Canada?” he asks.

“Beer, whiskey, rum, all sorts.”

“No, but how do you drink. I’m talking about your hard drinks. Do you add water, ice, soda? Do you sip it? Do you use big glasses or shot glasses?”

Bolor gets up, pulls a key out of a small drawer in his desk and turns to unlock the large metal cabinet at the far end of the room. The top half contains dozens of handguns; the lower portion houses the rifles. “Now I will show you how we drink,” he says reaching behind the rifles to pull out a bottle of vodka. “This is our little secret though.”

As Bolor closes the cabinet door, the guard returns with a bowl of stew, some Russian bread and another thermos of tea.

“Eat, eat, my friend.” Bolor eyes my bare feet, barks again to the waiting soldier, and I’m soon set up with new boots. “Now let us drink.” He passes me a half a mug of vodka. I down it in one long gulp, devour my meal and suddenly feel mighty fine.

“How come you speak such good English?” I ask. “Have you lived abroad?”

He claps a meaty hand on my shoulder and laughs. “We Mongolians can’t afford to go on holidays abroad. I can barely afford the staples such as vodka. No, my friend, I just had a very good teacher from San Antonio who taught at our military school.”

Two hours (and several drinks) later, the authorities decided what to do with the bizarre Canadian. I’m to be put up in a hotel, which I will pay for when Ben and Remy arrive. Army food will be brought to me three times a day. I feel like I’ve been granted entrance to heaven. My angels – two miniskirt-clad female officers – lead me to the hotel. It’s the same one I tried to check into that morning, and I smile at the frumpy woman behind the desk as the officers tell her that I’ll be staying there whether she likes it or not.

I follow the two officers, clumping up the stairs in my new army-issue boots, and settle into room forty-two. I sink onto the nearest of the two beds. It’s covered with two luxurious inches of matting – I feel like I’m stretching out on a cloud. After my chaperones leave, I splash cold, soapless basin water across my greasy body, collapse onto the bed and descend into a deep sleep.

The next morning, I’ve got a new goal – to let the rest of the world know I’m alive. After a breakfast of buttered bread, I’m left to myself. Outside the hotel, I take note of my surroundings for the first time. Sur Baatar is a busy border city, the railway station its central hub. Trains loaded with logs head off to China. Others, laden with copper ore, travel in the opposite direction into Russia to be processed. Most people in the city live in five to six-story concrete apartment complexes. The city looks like a ghetto stuck on the juncture of the Selenge and Orkhon Rivers.

I head to the post office where the public telephones are situated. On the expedition, we had our own satellite telephones, so I have no idea how the Mongolian phone system works. A man at a desk near the entrance beckons me over. He hands me a form and a pen. I look blankly at the Mongolian writing. On a calculator, the man indicates the call will cost one thousand togrogs – about a dollar US.

“I make telephone collect. No free?”

He taps firmly on the calculator. I pull out a roll of kodak film from my pocket.

“Trade film for phone call?”

He shakes his head. I leave. Without assistance, I probably couldn’t figure out how to make a collect call to Canada anyway.

But now it’s been eight days since I’ve last seen my friends. They know I took off in my kayak with little more than the pants I’m wearing and must be wondering, worrying, what the hell has become of me. I try to imagine what’s happened to them. Where are they? Are they all right? Surely with all the gear, food and and money they’re okay. But maybe the boat was damaged and they’re still stuck on the banks of the river. Still, since they have the two satellite telephones, I’m confident that everyone is back at home has heard about my disappearance – which is a mixed blessing. My mother likely had a breakdown when she learned her son had been missing for over a week with no food, gear or money.

A well-dressed woman bustles down the sidewalk towards me. “Internet?” I ask, my hands typing on an invisible keyboard. She nods and points to the north end of the city. I walk in that direction, ask more people the same question and try to triangulate the position of Suh Baatar’s elusive web terminal. Finally I find it – a single public computer at the city’s main library.

“Internet?” I ask the librarian.

The librarian seats me behind the computer. I don’t mention that the only currency I carry is film. I don’t want to loose my one precious chance to communicate with the outside world. In half an hour, I’ve composed messages to several people and told them I’m alive and well. I ask them to call Remy’s pager, which he checks periodically, and tell him that I’m waiting in Suh Baatar.

The librarian hands me a bill for 2,700 togrogs. I don’t care what happens now: She can’t pull the messages back out of the computer. If Ben and Remy don’t learn I’m here, we might never find each other. I hand her a pack of three films, and she shakes her head. “No money, just film,” I say. We face each other down for half an hour while she points to the bill and I hold my hands in the air. “Only film, I pay you when friends arrive. The film is much more valuable, so I make sure to pay later.” Finally, she tucks to film into a drawer. I point to the calendar and say, “Pay in three days.”

The following day, Lieutenant Bolor tells me the Canadian consulate in Ulaan Baatar has called. “You must come down to the base now, ” he says. “You will meet the commander.”

The room I’m led to trembles with authority. A large older man, who I assume is the colonel, sits in a throne-like chair behind a thick oak desk. Expensive rugs on the wall muffle the expansiveness of the 14′ ceilings. Two boardroom tables form a channel that channels attention straight towards the colonel’s desk. He motions me to sit down and tells Bolor to sit at the other table. Six officers enter, salute, and take a seat near Bolor. Three young women sit at my table. While we wait for everyone to arrive, the room settles into a hushed silence. Finally the colonel speaks and the pony-tailed girl beside me translates.

“You realize you no arrested?” she asks.

“Of course,” I say. “You guys have been treating me very well.”

“The colonel is concerned. He said the Canadian consulate call this morning. A Canadian journalist phone and ask about you. He say you are arrested at Russian border.”

“Oh, god. What kinds of rumours are circulating back at home? I imagine the newspaper headlines: “Canadian Rafter Faces Siberian Firing Squad.” Back on Vancouver Island, my mother must be catatonic with worry.

“We just want to make it clear. You must stay here because you have no identification but you no under arrest.”

I nod.

“We are also worried about your friends,” the pony-tailed girl adds. “If the water is strong, if they go over the Russian border by accident…” She pauses as she tries to convey the gravity of their situation. “Maybe shoot.”

The fenced-off border region between Russia and Mongolia is a no-go zone, and the guards stationed in the many lookout towers along the razor-wired line have orders to fire at anyone foolish enough to wander without authorization into the no-man’s-land. I don’t know how much danger Ben and Remy might face. I passed through the same stretch of water and the feeble current of the Selenge River at that point isn’t likely to overpower the raft and carry them past its confluence with the Orkhon into Russia. Ben and Remy have a good map and should know exactly where they need to hang a right to reach Suh Baatar. Still to be safe, I write a warning for them – adding emphasis with a crude drawing of a pistol – and later give it to some fishermen who patrol the confluence of the two rivers.

Suddenly the colonel’s cell phone rings, the ringer programmed with a trashy pop song. It’s the Canadian consulate on the line, so he hands the phone to me. Arianaa, a consulate employee, has been in contact with my mother, who received my email and has been imagining the worst – her half starved son trapped in a distant hinterland without a loony to his name, cast as the lead in a Mongolian remake of Midnight Express. She phoned the Canadian High Commission and asked if they could help me. They, in turn, contacted Arianaa, who tracked me down through the Suh Baatar police department – not, however, before a Canadian reporter began asking about my “arrest”.

I assure Arianaa that all is well. The army is feeding me, I’m sleeping in a hotel and I’m just waiting for Ben and Remy to arrive. I ask her to dispel any rumours that the army is brutalizing me.

The next morning I see a small boat on the river from my hotel window. It’s too far away to make out whether it’s the boys, so I pull on my boots and jog down the bank. A thunderstorm erupts and drenches me. As I draw closer to the boat, I can make out the unmistakable rhythm of someone hauling on long oars. It must be them. The army here will be relieved: I’m sure they think my friends are imaginary and the hotel bill will never be covered.

The deluge dissipates, and I see the boat more clearly. It isn’t our raft after all- just a fisherman in a steel boat.

Afterwards, Batjargal and Ihagvaa, the two female officers, take me to the local museum. We’re encouraged to touch the many hands-on exhibits – including a human skeleton dug up from somewhere, probably the local graveyard. I’ve finally figured out why I’ve seen so few animals on my journey: Mongolia’s wildlife has been stuffed and moved to the Suh Baatar museum. Bears, wolves, moose, elk, foxes and condors pose menacingly throughout the corridors and chambers. I suspect the taxidermist had a little too much vodka while he worked, though, as some of the disheveled specimens look as though he did little more than yank out their insides and stuff their hides with crumpled copies of the Suh Baatar Herald.

Later that afternoon, Bolor tells me that his commander wants to post a watch for Ben and Remy at the junction of the Orkhon and Selenge rivers. “He wants you to be there, too,” Bolor says. He rounds up Batjargal and Ihagvaa, an immigration officer and another soldier, and we leave in a Russian jeep with a bag filled with cigarettes, three bottles of vodka and a couple packets of candy for a Mongolian picnic. When we get there, a fisherman offers us a four-pound trout, which we roast over a fire.

The trip to the confluence takes us past many abandoned factories – disintegrating hulks of conveyor belts, loading cranes, huge pipes and caved in brick buildings. So much manpower went into building these industrial megaliths. Now they’re fading ghosts of the Soviet Empire.

No sign of Ben and Remy, though. As the light begins to wane, we return to town and I stare up at the concrete and brick apartment blocks. Almost every piece of literature I’ve read describes these buildings, and their Russian counterparts, with the same adjective: faceless. I’ve come to realize, during my time is Suh Baatar, that this attitude is a western misconception, a belief that the beauty in a home rests in the number of potted plants in the front. In Mongolia, the character of a home can be found within. The nomad’s ger, the quintessential Mongolian abode, could likewise be described as faceless: Every ger is identical in shape and colour, has no windows or potted plants, no decoration. Yet inside each of these homes, there’s a unique beauty in the generosity of the hardy people who carry on traditions passed down to them from before the time of Genghis Khan.

“See you tomorrow,” Bolor says, “Let’s hope we see your friends, too.”

We return the next day to where the same two rivers meet and swim in the cool water. Nearby a pair of fishermen stuff a pop bottle full of dynamite, hurl it into the river and wait for the dead fish to rise to the surface – without any luck. Hard times and Russian influence have eroded Mongolian’s traditional disdain for seafood, and their explosive angling techniques have rapidly depleted their once-teeming rivers. Finally, at eleven that night, I spot a familiar yellow raft approaching.

“Ahoy mates!” I yell.

“Is that Colin?” I can recognize Ben’s voice as it carries across the water.

The raft draws to shore, and my friends leap from the boat to greet me. Remy announces in a booming mocumentary voice; “And at last, after twelve days, the team is reunited!”

We carry their gear back to my hotel and swap tales of the past two weeks. Ben and Remy waited for two days at the site of the capsize and then continued down river to Hutag – arriving just hours after I’d left. In the same desolate town where I was reduced to begging for bread, my friends met a pair of Canadian missionaries who took them in. While I ate stinging nettles and bird fetuses on the banks of the mosquito-infested river, Ben and Remy gorged themselves on chocolate brownies and pancakes with peaches. They stayed in Hutag long enough to carve new oars for the raft, rejig the broken oarlocks and repair the solar panel that charged the satellite phone. Then, three days after arriving, they learned from the shopkeeper who’d begrudgingly given me the package of bread that she had met a half-starved foreigner, and so they set off for Suh Baatar to search for me. All along the river, they encountered Mongolians who’d seen the strange Canadian in the yellow kayak. Finally at the confluence of the Selenge and the Orkhon rivers, they received (and appreciated) my warning note about the danger of crossing the Russian border.

Together again, we still have over four thousand km of Siberia to pass through to complete our source-to-sea journey down the Yenisey River. In many ways, our expedition has barely begun. Still, once lost in the wilds of Mongolia but now reunited with my friends, I feel for one prolonged moment, as though my journey is already over.

Magazine article originally published in Explore Magazine.