Derek Hatfield – The World’s Most Gruelling Race

August 2007

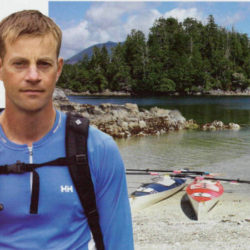

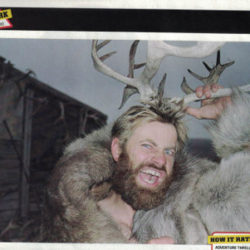

Derek Hatfield will compete in the 2008 Vendée Globe and, if successful, will be the first Canadian to complete the race. (Courtesy of www.spiritofcanada.net)

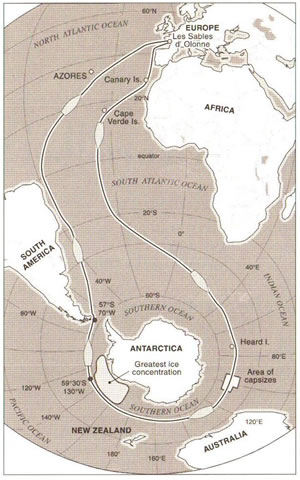

The Vendée Globe, around-the-world sailing race, is dubbed the world’s most gruelling challenge. Beginning and ending at the port of Les Sables d’Olonne, France, the course heads south into the infamous Southern Ocean where temperatures are freezing and hurricane-force winds frequent. The boats are singlehanded and stopovers or outside assistance is not allowed.

The race generally takes 3-4 months as the sleek performance boats move at speeds often exceeding 20 knots. The average speed of the winning boat is usually above 11 knots (22 km/hr). Conditions in the southern seas are so horrendous that frequently boats succumb to the ocean’s forces. Rescues are next to impossible in the regions where there is no commercial shipping and beyond the range of land-based helicopters.

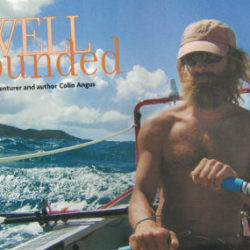

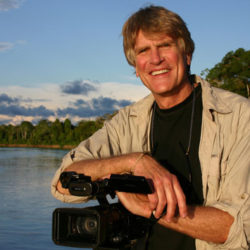

Derek Hatfield has custom built the sixty foot Open design he will be competing in. (Courtesy of www.spiritofcanada.net)

Derek Hatfield of New Brunswick will compete in the 2008 Vendée Globe and, if successful, will be the first Canadian to complete the race. Only one other Canadian, Gerry Roufs of Quebec, has taken on this challenge, and sadly he was lost in the Southern Ocean.

Derek has custom built the sixty foot Open design he will be competing in. In November 2008 he will join 27 other boats in France to commence the circumnavigation. Other nations competing in this race include Australia, China, Italy, the USA and Japan.

Unfortunately for Derek Hatfield, competitive sailing sits on the back burner along with soccer, as far as Canadian interest is concerned. Most Canadians were unaware of Gerry Roufs efforts in 1996 until his demise, which became front-page news.

Let’s hope this upcoming race is different, and the Canadian media and public take interest in a determined Canadian representing our nation in the world’s toughest race. This sport has it all; suspense, danger, drama, and toil. We’re proud to have you in the Vendée Globe, Derek, and we will be cheering for you all the way around!

Below is an excerpt from Godforsaken Sea by Derek Lundy (Viking 1999) which gives a flavour for the Vendee Globe:

“Until Christmas Day, 1996, the race had been a typically robust version of previous Vendée Globe and boc races. If anything, it had been easier on the competitors than most of the earlier events. None of the collisions with flotsam or ice in this Vendée Globe had put the sailors’ lives on the line. It was true that the Southern Ocean had behaved as usual-its chain of low-pressure systems moving relentlessly along the racers’ path. Storm — and often hurricane — force wind had piled waves up to heights of fifty or sixty feet. At times, the boats had surfed down wave faces at thirty knots, almost out of control. They had struggled through the dangerous and chaotic cross-seas that followed quick changes in wind direction and had been knocked down often. For several weeks, the skippers endured this trial by wind and cold, ice and breaking waves, skirting the edge of catastrophe as they threaded their way through the great wilderness of the southern seas.

True, it was still a long way to Cape Horn. The greater extent of the Southern Ocean still lay ahead for most of the boats. There was a lot of time left for something to happen. At some point in every one of these races, most often in the Southern Ocean, a sailor’s life becomes problematic, hangs by a thread. Sometimes, a life is snuffed out: by inference at first, as contact is suddenly ended; later with certainty, as enough silent time goes by or the searchers find a boat, drifting and unmanned. Some names: Jacques de Roux (1986), Mike Plant (1992), Nigel Burgess (1992), Harry Mitchell (1995) — a few of the ones who have been wiped off the planet. Who knew exactly how? What were the circumstances? An unendurable rogue wave capsizing the boat? Ice? Or a sudden, treacherous slip over the side and into the sea, followed by a final minute or two treading the frigid water, watching the boat (with acceptance? anger? terror?) intermittently visible on the wave crests, surfing farther and farther away, its autopilot functioning perfectly.There hadn’t been any of that yet in this Vendée Globe. But the dragons were certainly there. The “quakin’ and shakin’ ” was about to begin. During the twelve days of Christmas, the race changed utterly.

From approximately the other side of the earth, at about the same latitude north of the equator as the Vendée Globe sailors were south of it, five hundred miles from the North Atlantic Ocean, sliding deeper into the Canadian winter, I followed the race. There was the occasional wire story in the Toronto newspapers. Nothing much on television. The Quebec media, especially the French-language side, provided more coverage because the race originated in France. More important, one of the skippers, Gerry Roufs, was from Quebec. He’d grown up in Montreal and had sailed at the Hudson Yacht Club, just outside the city. He’d been a junior sailing champion — a dinghy prodigy — and had sailed for several years as a member of the Canadian Olympic yachting team.

I was intrigued by the Vendée Globe for a couple of reasons: I’d been an avid — although amateur — sailor myself over the years, and I found it impossible not to be fascinated by the race’s audacity — its embrace of the most difficult kind of sailing (single-handed), through the most dangerous waters in the world (the Southern Ocean), in the most extreme form possible (unassisted and non-stop).

I also felt a connection to the race because of Gerry Roufs. He was the first Canadian to have entered the Vendée Globe, and he had a good chance of winning. There was a small but significant affinity between us. Like me, he had trained to be a lawyer, and had then found something different to do with his life, though in his case, something precarious and uncertain, far removed from the affluent safety of the law. After a year, he left his law practice to become a professional sailor, and spent the next twenty years working towards his eventual membership in the single-handed, round-the-world elite.

For more information on Derek Hatfield and his Vendée Globe quest please visit :