A year after my Google discovery, in 2002, I was feeling philosophical. Like so many people, I was struck by the paradox that the human struggle for advancement was killing the planet that sustains us. The scientific community agreed that global temperatures were rising as a direct result of human intervention. If this pattern continued, within decades climatic conditions on our planet would change at an unprecedented rate. Coastal cities would flood from the rising oceans, lush agricultural land would turn into desert, and storms would increase in both strength and number. Millions would die from displacement and starvation.

Despite this apocalyptic forecast, the solution remains simple. Humans need to reduce their emissions of so-called greenhouse gases. The one hitch: such conservation may result in a short-term dip in the global economy. Quality of life–as defined by economists–might decline, especially for those who prefer driving their SUV to fetch a carton of milk rather than walk or ride a bicycle. The immediate benefits, however, would be less air pollution, a healthier population and a rise in innovative technologies and industries that cater to a less destructive society. Most important, a reduction of emissions would ensure atmospheric equilibrium and ultimately benefit all of our children, and their children, and their children’s children.

These are the facts.

Although the appropriate course of action is clear, our society has chosen a different route. Total greenhouse-gas emissions increased by 50 per cent between 1970 and 2000. This trend is not changing.

Like many socially conscious citizens, I did what I could. I used my bicycle or public transit for almost all my transportation needs. I kept the heat low in my home. I tried to minimize my reliance on the power grid. It was frustrating, however, that despite the changes and efforts made by a few, overall greenhouse emissions steadily continued to rise. What else could I do to make a difference?

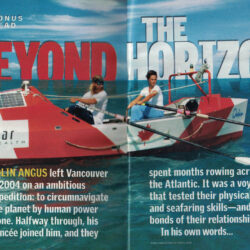

I revisited my daydream about a human-powered circumnavigation of the planet from a more serious perspective. Such a journey would garner much publicity, and this media attention could be leveraged to promote zero-emissions travel. If I could make it around the entire planet using my own muscles, it might inspire others to ride their bikes to work or walk to school. Suddenly, I realized that this expedition would be more than just a once-in-anyone’s-lifetime adventure. It could also be a loud and clear statement about the urgency of climate change, an action that would speak louder than mere rhetoric about the issue. I could chronicle the expedition in a book to convey the message to a wide audience.

I ran my finger over the surface of a globe. I tried to imagine the easiest route and how I might traverse the various regions. By the middle of 2002, I had decided that I would do it. I would attempt the first muscle-powered journey around our planet.

***

I felt somewhat like a child who declares he is going to fly to the moon. Although I had stated to myself that I would do it, and had every intention of carrying through, I still struggled to believe I would be successful. As the child starts clearing toys from the launching area, I began tapping on the computer, doing Google searches to glean some rudimentary information about what I was up against.

Because of these extreme nagging doubts, my initial preparations weren’t accompanied by the usual enthusiasm I feel when striving for a more simple and achievable goal such as building a small boat or planting a vegetable garden. Instead, I laboured on the project simply because I said I would. It felt as though I were begrudgingly working for the small part of my brain that felt success was a possibility.