A Russian stealth vessel slipped quickly but silently into the harbour, unnoticed by all but us. The accompanying silence spoke of technology the Canadian military could only dream of. Even the shape of the vessel, all obtuse angles and linear planes was formulated to elude the most sophisticated radar. A hatch slid open revealing the steely gaze of the skipper. He glanced our way, tossed a casual wave, before guiding the craft in an arcing curve until it nudged gently against the dock.

“Wow,” Julie said staring across the water, “Do you think he’ll let us take it for a spin?”

“Wow,” Julie said staring across the water, “Do you think he’ll let us take it for a spin?”

Julie’s words snapped me from my reverie. The boat we were watching was in fact, a human powered vessel designed by Greg Kolodziejzyk, a Calgarian adventurer planning on pedaling his boat to Hawaii. The destiny of the tiny ship was already colourful enough that it didn’t require further embellishment from my overactive imagination.

Depending on your definition of speed, Greg Kolodziejzyk could easily be labeled as the world’s fastest human. He holds two Guinness World records and has travelled further in a day using muscle power alone than anyone else. He achieved this in 2005 using a specially-designed recumbent bicycle, and travelled a thigh-twitching 1000 km in a single day. Talk about a good day’s run. Greg has also voyaged the greatest muscle-propelled distance on flat water using a sleek pedal-powered trimaran clocking 245 km in 24 hours.

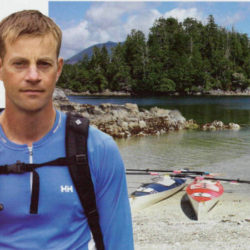

In preparation for Greg’s latest challenge, to pedal across the ocean to Hawaii, he had his boat in Ucluelet, BC for sea trials where Julie and I had come to check it out. With us was Roz Savage, an ocean rower from England who was visiting us during a hiatus from her current challenge rowing across the Pacific Ocean. We were a motley collection of ocean wanderers, fueled my muscle, motivated by imagination, and momentarily brought together on a listing dock off Vancouver Island.

Heavy raindrops pitted the water’s surface as Greg showed us around his vessel. A tiny bed graced the rear of the boat, and the central area was equipped with a seat and pedals. A small handle on the starboard side operated the rudder, and electronic navigation and communications equipment surrounded the pedaling station. The forward half of the diminutive vessel would hold supplies for the multi-month voyage.

We each took turns maneuvering the vessel through the harbour. The boat moved easily through the water with a comfortable cadence at the pedals, and light nudges on the steering handle shifted the boat to the left or right. I upped my effort to a sweat-inducing whirl, and the speed steadily climbed to 5.7 knots. It’s a well-built boat, and undoubtedly Greg will make excellent time as pedals towards his hammock on a distant beach.

Van Isle 360 – Preparations

With our own adventure plans, the excitement is building as the mid-June departure date for my Vancouver Island circumnavigation nears. The objective is to cover the 1150-km distance in a rowboat in 16 days or less, which requires travelling at least 72 km/day, often in adverse conditions. To stand any chance of achieving this goal good preparation and training are essential.

The current speed record for circumnavigating Vancouver Island is held by English kayaker, Sean Morley, who lapped the island in just over 17 days. To further add spice to the recipe, we’ve received word that Thunder Bay native Joe O’Blenis will also be attempting to break the record this summer in a kayak. Super-paddler O’Blenis was the former record holder, and he is determined to reclaim his title as Van Isle speed champion.

What’s faster between a rowboat and a kayak? There is no definitive answer to this question. Looking at performance competitive craft, generally rowing shells are fastest followed by kayaks and then canoes. This, however, is in controlled calm conditions, and the open ocean is a completely different paddle pot. A kayak would likely go faster in messy cross seas while the power of a rowboat might provide an advantage going into headwinds. And just because rowing is faster for the short distance doesn’t necessarily mean it is for the long haul. Caloric burn per hour is greater in a rowboat for a given speed because so many large muscles are being used simultaneously, meaning more energy must be metabolized.

The chances of my success are moderate, requiring a combination of luck, good weather, no injuries, and a lot of toil. Regardless of whether the journey is completed in less than seventeen days, it will offer a super opportunity to explore the inaccessible (by land) nuances of Vancouver Island, and help chisel off any left-over winter flab.

I’ll be using the same rowboat that was used in our Scotland to Syria expedition – a closed 18’ vessel with a sliding-seat rowing system. Camping gear, food, water and other equipment can be packed in the watertight compartments. There is little habitation along the rugged west coast, so it is important to be self sustained while rowing through this region.

In order to minimize the distance travelled strategic navigation is essential, and a GPS will be used to ensure straight-line headings between points. Off the NW coast of the island, there are numerous offshore reefs, and irregular waves which are reflected off the precipice-lined shoreline. Here it is essential to be vigilant with navigation. Reefs 5-10 feet below the surface remain invisible until massaged by an extra-large swell. The preceding trough would momentarily lower the water level, exposing the pinnacle before the following wave collapsed over the rock. If you happen to paddle over one of these “boomers” an otherwise pleasant day can quickly go downhill.

Being prepared for all scenarios is essential. This involves envisioning every problem that could occur, and thinking through a solution. There are the more basic problems like how to deal with a broken oar or other mechanical concerns, but also more serious issues like being run down by a fishing boat or having the boat wrecked on a reef a kilometre from shore.

The boat is fully sealed meaning that if it does capsize, it is a simple process to right and continue on. It doesn’t even require bailing as all water drains from the cockpit as the boat is righted. If the watertight integrity of the boat is compromised, a small inflatable life raft will offer a secondary shelter from the sea, and a wetsuit will assist in warding off hypothermia.

A tracking device will be used, and people interested in following the journey real time will be able to do so online.

Angus Rowboats:

It’s been a busy month for us since we’ve started our new business selling plans and kits for our Expedition model rowboat, which is proving to be very popular. We’ve been sending plans around the world – from Australia to Germany to France, and look forward to eventually seeing the boats out on the water. We’re currently designing two new models – an open 16’ based on the lines of a traditional wherry fused with modern elements to enhance performance, and a 24’ open-water racing scull which should be able to exceed 15 km/hr.

The new boats have been designed in the computer, and the next step will be creating prototypes to test their performance. We’re hoping to have the new boats available this fall.

More information can be found at www.angusrowboats.com

Other Adventures:

All sorts of exciting adventures are currently going on right now. Roz Savage is about to embark on the final leg of her rowing voyage across the Pacific Ocean. She departed from Tarawa yesterday, and if all goes well, will end up in Australia in a few months.

Speaking of Australia, Ozzy, Jessica Watson, is all but finished her non-stop solo sailing circumnavigation. The sixteen-year-old is now off the west side of Australia, and just has to continue around to Sydney to become the youngest to sail around the world. It’s an incredibly challenging feat for someone so young. She’s expected to reach Sydney in early May.

Our featured adventurer this month is Andrew Skurka, National Geographic’s Adventurer of the Year for 2008. Skurka is an endurance athlete, and he’s just commenced on a trek of mind-boggling proportions. The only place in North America wild and woolly enough for Skurka’s latest trip is the Yukon Territories and Alaska, and that is where we can currently find him…