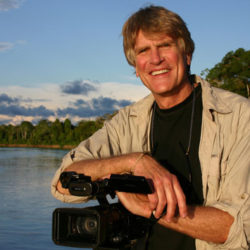

This weekend Colin will be presenting at Whistler’s 2017 Multiplicity. It’s an epic night of adventure tales and on stage he’ll be joined by Jon Turk, Sherry McConkey, and others. Julie spoke about her adventures at Multiplicity previously and it’s great to return.

Multiplicity is a flagship fundraiser for the Spearhead Huts Project; it’s been described as “a TED Talk on adrenalin,” and “the most inspiring night of the year.”

Read Colin’s full interview with Mountain Life and check out the highlights below.

Welcome to MULTIPLICITY. Let’s start by talking about your presentation?

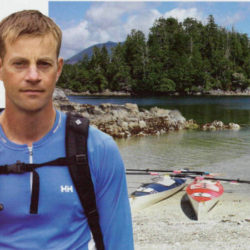

Thanks, I’m looking forward to it, not only for the presenters, but also for the audience. Such an inspiring crowd in Whistler; it will be like speaking to the converted. What I’ll be talking about mostly is a race I did up the West Coast of Canada, the Race to Alaska. The starting point is in Port Townsend, Washington, and it goes 1,200 km to Ketchikan, Alaska.

You’ve done a lot of water-based adventuring. What is it about this race you found so inspiring?

It’s one of the longest maritime races in North American and it goes through some pretty amazing environments. You’ve got the whole Great Bear Rainforest and the Inside Passage. It’s very beautiful scenery, but at the same time it’s very grueling as far as the race is concerned—you’re just pushing as hard as you can. The two things I love about are the area it goes through, and the other being trying to do well in a race. My background is adventuring and expeditions, in particular water-based journeys. The idea of designing a boat and competing in this race was pretty exciting.

So you designed and built a boat specifically for this race?

It’s called the RowCruiser. It’s almost 19 feet in length, designed to both row well and sail well. It’s based on an earlier design and can move at about four knots comfortably under row, and can go up to about 12 knots if you’ve got a good wind blowing. The beauty about Race to Alaska is anything goes as far as what mode of propulsion you want to use, as long is there’s no motor involved. It’s a perfect blend of using both wind and muscle power.

I heard there was a bit of a hiccup in 2015 when the boat fell off a trailer?

That was sort of the disheartening part of all this. I was also supposed to be in the 2015 race. I spent a year designing and building this boat, going through every single detail. We were spending a few months before the race familiarizing ourselves with the boat—I was going to go with a partner that year. One day, after one of our training sessions, I forgot to tie the boat down on the trailer. It wasn’t until I heard a sort of shifting noise as I was going around a corner that I realized, Oh no, I forgot to tie down the boat. A second later—CRASH. So that was it, I was out for the year; there was no way we could get it repaired in time. It was a pretty sinking feeling. You put that much effort into doing this race, and then you have to pull out for whatever reason. But it’s the actual effort that goes into creating the vessel; it’s painstaking all the details that go into it.

But the sinking feeling didn’t last long?

Like many things, it was a blessing in disguise. I think it worked out for the best. I signed up for the next year’s race, fixed up the boat and decided to do it solo. After more research and training, I ended up in the 2016 race, and all went well. I ended up winning the fastest boat under 20 feet, and was also the fastest solo boat. After all we’d been through the previous year, it was a great feeling. It took 12 days to get from Victoria to Ketchikan.

I understand you were the first person to circle the globe by human power?

That’s right. It was quite a few years ago, in 2006, when I completed that one. Over the years, my wife and I have done about a dozen adventures all together, but that one was a doozey. Everything else tends to get overshadowed by the circumnavigation. That was two years of just slogging.

What was the inspiration for that?

I was always fascinated by the concept and intrigued that nobody had done it before. People had gone around the globe in every imaginable mode of transportation, except by human power. The idea of using the most basic form of propulsion—human muscle—to start in one spot and keep going until you came back to it again, is pretty simple in concept, but obviously actually doing it is such a hugely complex and gargantuan undertaking. We crossed the Atlantic and the South Pacific From Lisbon to Costa Rica in a rowboat.

You made a descent Amazon River as well?

Yeah, we did that in 1999-2000 in five months. It was an Australian a South African and myself. The first team to do the Amazon did it in 1986; there’s a book about it, a New York Times best seller called Running the Amazon. I read that book and was hugely inspired by it. You think of the Amazon as being this slow, meandering river through the jungle, but in the upper headwaters, it’s very different than that. It’s starting out in the world of snow and ice and granite, through these narrow canyons that made it very challenging. After reading that book, I was really stoked and wanted to do it myself.

These are some no-joke adventures, where did you first catch the bug and what motivates you?

Well, I guess what motivates people to do anything? It’s all different desires and ambitions. For me, it was an evolutionary process. The whole adventuring thing started out as a dream I had as a little kid. My very first adventure was a five-year sailing trip, and I decided I wanted to do that by the time I was 12. I’d read a book called Dove, which is about a 16-year-old kid who sailed around the world back in the late ’60s. His name was Robert Lee Graham. I just thought it was so cool, so exciting, that I wanted to do that myself. But I didn’t really grow up with a background that afforded one to have that sort of opportunity. I was raised by a single mom who had four kids in Port Alberni on the West Coast of Vancouver Island where there were zero opportunities, really, to go sailing, or to earn the type of money you’d need. But I hung onto that idea, and saved up my paper route money.

Paper route money?

I met a friend who thought it was a pretty cool idea, too. So we started planning the trip together. We bought an old beat up boat and spent the next five years sailing it. That was sort of the eye opener. I was a shy kid, who’d never really done any traveling, people probably thought I was the last person who’d go on a crazy adventure. But having done it, making this dream become a reality, I found it hugely inspiring. I felt much more capable at that point. I was a pretty clueless kid when I’d left. I didn’t really know anything. No one had taught me anything mechanical, but by the time I’d finished that journey, I felt much more confident dealing with logistics and solving problems

Tell us about the hurricane?

When my wife and I were rowing across the Atlantic, it was quite unfortunate. We’d spent a lot of time analyzing the weather data compiled over the last 100 years, and we were actually in the part of the Atlantic where they have the least amount of storms, never mind hurricanes. It should have been easy going. But that year, there were more anomalies and more hurricanes than any year up until present. We were informed that Hurricane Vince had formed in the Atlantic and was coming straight for us. That was just a few weeks after leaving Lisbon, so we weren’t far from Europe at that point, and the hurricane ended up coming right over our boat. It’s pretty intimidating, being in a tiny rowboat made of 1/4 inch plywood, with a storm that has the power to decimate a city coming straight at you.

Not a pleasure cruise at that point, eh?

The boat was very seaworthy, and could handle almost any conditions, but still, as far as we knew no one had ever ridden out a hurricane in a rowboat before. The waiting game was almost as bad as the storm itself. You’re all alone in the ocean, all the other boats had left—they had these big diesel engines, but we didn’t have that speed—we were just sitting ducks.

What do you hope the audience takes away from your presentation?

Overall, I think the biggest thing is for people to feel that they have confidence to go out and do whatever it is they’re passionate about. For me, one of my passions is extreme physical challenge. That’s not for everyone, but often when people are going through life, they feel these parameters, these restrictions that society or peers or parents impose upon you. Often people don’t end up going in the direction that would truly make them happy and or fire up their passion. The message I want people to take away is you’re on this planet once, and I always feel so fortunate to live in the time that I do, and the place that I do, where really there are no shackles whatsoever. The sky’s the limit and you can do whatever you want to do. The last thing you want to do with the brief moment you have on this planet is to not go out and reach your full potential because of conditioning or peer pressure.